Blue and White Nile

Introduction

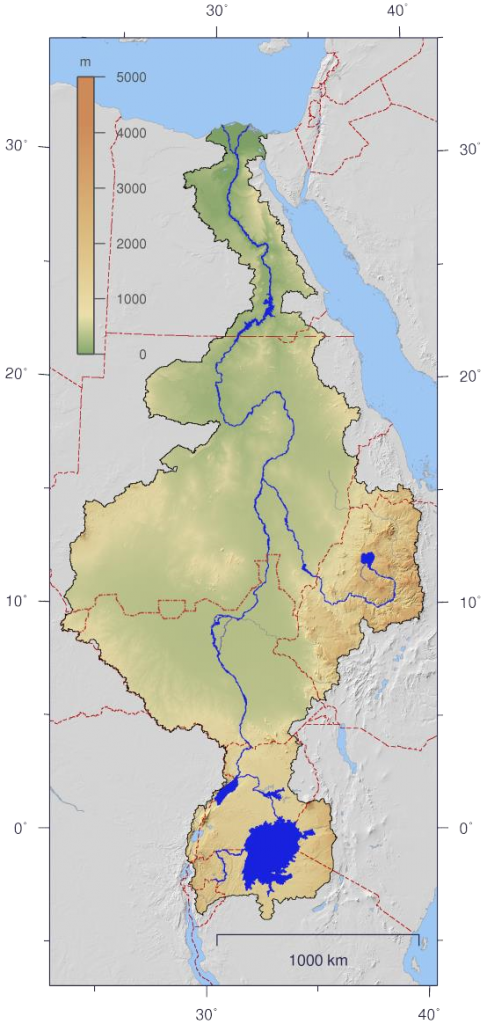

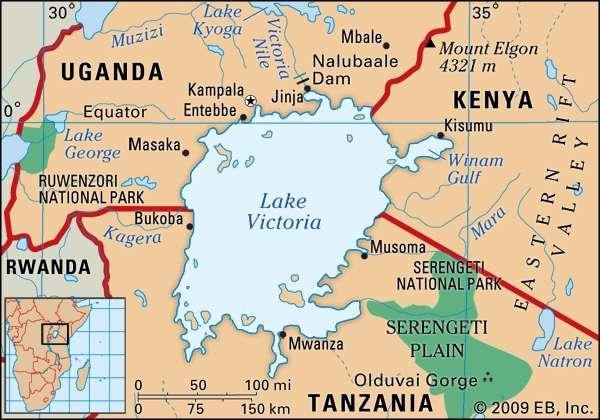

Sailing on lake Tana in Ethiopia is a true experience. Numerous ships, a lot of packs of household goods, merchandise, animals and people are on their way to their destination. Where do they go and where do they come from? This vast lake is the starting point of the Blue Nile. With great force, the water has been searching for the most suitable route to Khartoum for millions of years. From this metropolis, the White and Blue Niles flow together to Cairo and then pour their precious water into the Mediterranean Sea. The White Nile departs from Lake Victoria and winds its way through the swamp of South Sudan, on its way to Khartoum. The water of the Nile was and still is the basis for the lives of millions of people.

Lake Tana is the starting point for Mathieu’s virtual journey along the Nile. On his route he virtually follows the trail of people who lived there briefly or for a long time in a grey past. Archaeologists have described numerous objects used by the inhabitants for their shelter and for the acquisition of their means of subsistence. Being able to have water and nutrition is for humans, animals and plants the basis for living on this globe.

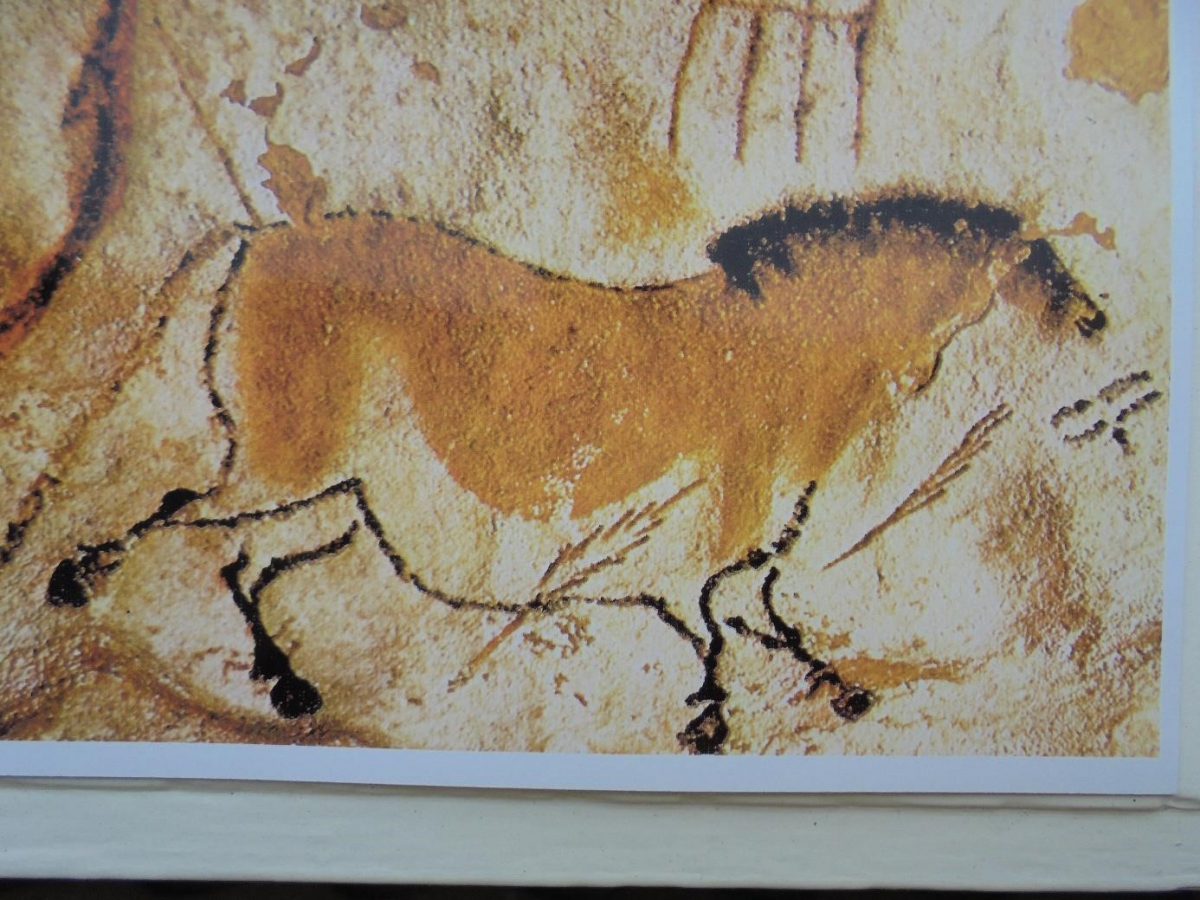

On this virtual journey along the Nile, Mathieu also pays attention to cultures of people who have left their mark here in the past 10,000 years. Archaeological research in various settlements along the Nile has produced beautiful art expressions over the past 150 years. Archaeologists have described their research and shown many images illustrating their research.

Nubia

In Khartoum, the White and Blue Niles merge and the main stream of the Nile continues its long route to the Mediterranean Sea. From here to Assuan there are six waterfalls in the main stream of the Nile. The catchment area of this mighty river has probably been inhabited by humans and animals for 300,000 years, surrounded by lush vegetation. Archaeologists have found tools from residents that will have been widely used for hunting, fishing and preparing meals 70,000 years ago. Pots and pans and other ceramic products were dated by the researchers to 40,000 years today.

On his journey, Mathieu will limit himself to the traces found in this catchment area of the Nile and its vicinity. The Nile was and still is an erratic river, characterized by heavy flooding and declining water levels. Especially from 5000 years of today , the landscape of Nubia outside the catchment area has gradually turned into a barren desert.

The Nubian population lived mainly in small settlements, south of the third waterfall of the Nile. They took advantage of the opportunities to catch a lot of fish. Their dead were given a cemetery and also means to save themselves in the wide cosmos. Some deaths were clearly better anticipated than others. In Joachim Willeitner’s book : NUBIEN – Monuments between Assuan and Khartum, the necropool Kadada is listed at Schendi, 180 km north of Khartoum. Here 3000 graves were found, where dead from a long period of time were assigned their final resting place. It is noteworthy that no traces of settlements, nor of necropoles, were discovered during the preliminary investigation in the construction of the Assuan dam. Apparently, the surroundings of the first cataract (waterfall) were not attractive to settle there. Few traces were also found further south of Assuan until the second cataract. It is assumed that nomads passed by here, but that there have been no residents with permanent places to live in this area. However, diverse settlements have been found south of the third cataract to the sixth cataract at Khartoum. Here were many more opportunities to practice agriculture, in addition to fishing and hunting, to enable the inhabitants to make a living.

Here they also found large cemeteries and numerous items that were given to the precious dead for their timeless wandering in the cosmos. The head of each settlement had sufficient resources to manage the goings-on of the inhabitants. About 8,000 years of today , many drawings were scratched into rocks, especially at the second and third cataract.

These were discovered by researchers and marked as high-quality artistic expressions of the Nubian people. Images of ships show that the Nile was also used to transport goods, animals and people. There was certainly fear for hippos that posed a threat to fishermen. Mathieu saw these dangerous animals in Lake Tana in Ethiopia. He could imagine that mythical powers were assigned to the hippopotamus. The goddess Taweret is depicted as an upright pregnant hippopotamus with heavy drooping breasts. The hippopotamus was known for protecting her offspring. Taweret was revered as the patron goddess at birth and the first suckling time of children. She was also depicted with features of a lion or crocodile, to drive out evil spirits and demons. Taweret can be found on countless amulets and can be found on the worship of this goddess.

Numerous gods and goddesses have played an important role in the lives of families who have lived along the Nile or in the vicinity of this mighty river. In mythology you will find stories about gods and demons all over the globe where people stayed. Also, animals and birds were often revered that could provide protection against dangers and ailments.

Around 1985 Mathieu was invited to Port Sudan to visit the family of a colleague with whom he was able to work closely for several years. He had grown up in a village near the second cataract and had always managed to maintain good contacts with his parents and his family. He lent Mathieu a book written in the English language about the rich history of the Nubian people. Mathieu did not remember the title, but some memories of the content. These mainly concerned the washing water of the Nile, with the positive result that the fertility of the country was promoted. The families in the settlements along the Nile will have gratefully taken advantage of this.

Attention was paid to the wealth of gold in Nubia that the Pharaohs of Egypt were interested in. The armies of these Pharaohs advanced to the land of Nubia mainly to rob gold, wood and cattle. Thousands of slaves were also taken north to build extensive structures and pyramids.

Return to Ethiopia

In Ethiopia, a serious conflict around Tigray threatened in 2020, prolonged in 2021. The government of this great country in the Horn of Africa, demanded that the leaders of Tigray continue to recognize the authority of the federal state. Ethiopia’s president had finally made peace with Eritrea in 2018. In 1998, a fierce war was waged for limited territory on the border of both independent states. Eritrea had opted for independence after the expulsion of the DERG-regime under Mengistu. Mathieu saw many soldiers leave for the front in Addis Ababa in 1998. In a short period of time, some 90,000 young people were killed in this violent, senseless conflict. In 2020, another civil war in Ethiopia threatened, with unpredictable consequences.

Ethiopia is home to some 110 million people; of these, around 4 million will now live in the capital Addis Ababa. In several villages and towns there is a risk of famine and the COVID-19 pandemic also poses a serious threat. The largest state, Oromia with a population of 40 million, may also continue to seek independence in the coming years.

The grain tef, needed for the injera, daily food in Ethiopia, is twice as expensive as sorghum; many households cannot afford the luxury of tef. This concerns especially the less fortunate households in Addis Ababa and in numerous villages and smaller urban centers. Over the past 50 years, there have been some major famines in Ethiopia. Sad images of these disasters are scattered all over the world; thousands of families were hit hard and millions of animals succumbed to the shortage of water and available vegetation.

Mathieu was able to observe, 25 years ago, the situation with the shelter and facilities of families in the urban area of Addis Ababa. Also in Debre Zeit,40 km south of the capital. He remained amazed at the cordiality with which he and his guide Gullilat were received on residential yards. He certainly owed that mainly to Gullilat. He had been trained as a teacher and had been head of the union of teachers in Ethiopia for many years. He visited neighborhoods where former colleagues lived, but it was heartwarming to witness the friendships he had built in recent years. Mathieu also visited his family. He observed the poor comforts of this family in a garage of an apartment building. Gullilat had a building plot of a housing cooperative and build there a house for his family.

With him, Mathieu walked for many hours in the settlements in the nearby surroundings of Addis Ababa and Debre Zeit. The meagre existence on holdings of less than two hectares was mainly due to the fact that the amount of precipitation needed for the operation of their holdings was unpredictable. Rain was of great importance for the production of tef, sorghum and vegetables. These products could be sold well in the urban environment and were also partly necessary for their own food. However, children turned their backs on poor agriculture and sought refuge in the rapidly expanding metropolis of Addis Ababa. As an urban and rural planner, Mathieu was involved in the realization of a pilot project in Addis and Debre Zeit. If this would offer good prospects, the Netherlands was expected to make a substantial contribution to the spatial redevelopment of the urban environment.

Unfortunately, in 1998, the disastrous war between Eritrea and Ethiopia, which has already been mentioned, broke out. That’s how this perspective disappeared from view. Especially with the support of Germany and China, a modern metropolis was built after 2000. You can question that. Certainly, the interests of many disadvantaged families have been set aside in the acquisition of building land and the construction of residential towers of Chinese allure. There was also an extremely difficult problem with the borders between Region 14 – Addis Ababa and the Oromia region. The regional government of Oromia defended the interests of the farmers, who threatened to lose their land by expanding the territory of Region 14.

Around 1980, an Italian urban planning agency in Milan had submitted an interesting vision for the spatial design of Addis Ababa and its wider surroundings to the DERG regime. However, after1991, studies that had been realized under this regime were set aside. But Mathieu had looked at these propositions in detail. The bottom line was that within a radius of about 50 km around Addis Ababa train station, the natural growth of the population and also all migrants could be accommodated. With proper management of the available water in rivers and the construction of some dams, it would be possible to produce sufficient food for all families in this urban and rural environment.

After 2000, however, Ethiopia offered chances for international investors, who leased agricultural land for many years, mostly for the cultivation of export products.

Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD)

The “GERD” is the largest dam in Africa in the Blue Nile. Over the past decade, it has sharpened relations with, Sudan and, above all, Egypt. The construction of the GERD could be achieved in 2022 . Ethiopia decided in 2020 to close the drain taps and partially filled this large dam. The supply of water from the Blue Nile is crucial for the collection of water in Lake Nasser in the South of Egypt. The Assuan dam was built to supply the Nile water to the farmers and cities in Egypt on a planned basis. The livelihood of the population in Egypt, also over 110 million inhabitants , with at the large metropolis Cairo of 20 million, is seriously endangered. No agreement has till yet been reached between Ethiopia, Sudan and Egypt. The African Union is actively involved in this conflict.

Numerous reports have been drawn up on the distribution of the Nile water, but a clear agreement between the three countries concerned has not yet been concluded in 2021. The GERD dam will double the electricity supply in Ethiopia. This offers numerous opportunities for entrepreneurs and households. Farmers in Egypt have already restricted cotton production and switched to fruit and vegetables for the local market. They fear that less water will become available in the near future. Because it is not imaginary that farmers in Ethiopia who live along the borders of the Blue Nile, from the Tana lake to the GERD, will demand also more water for irrigation.

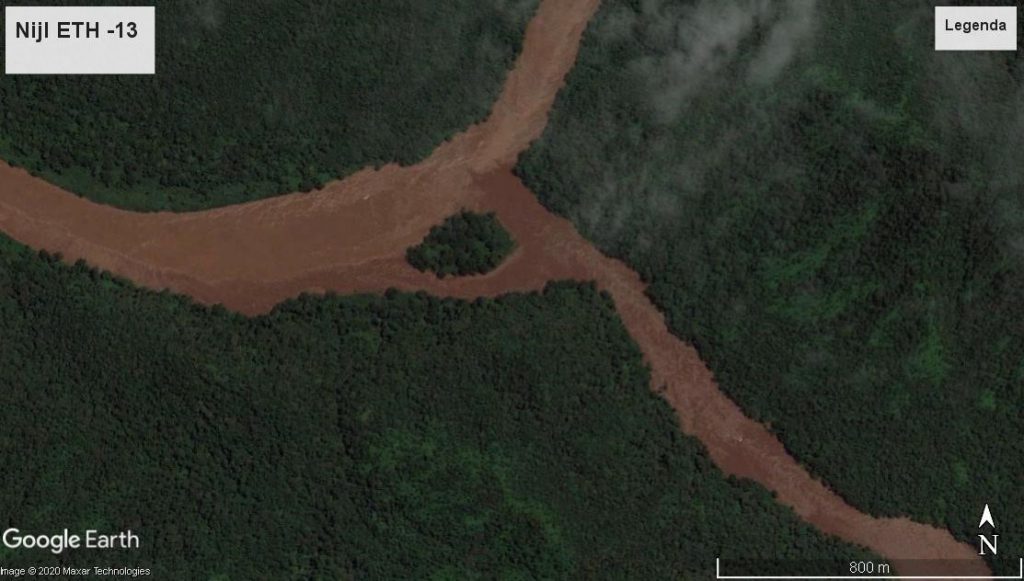

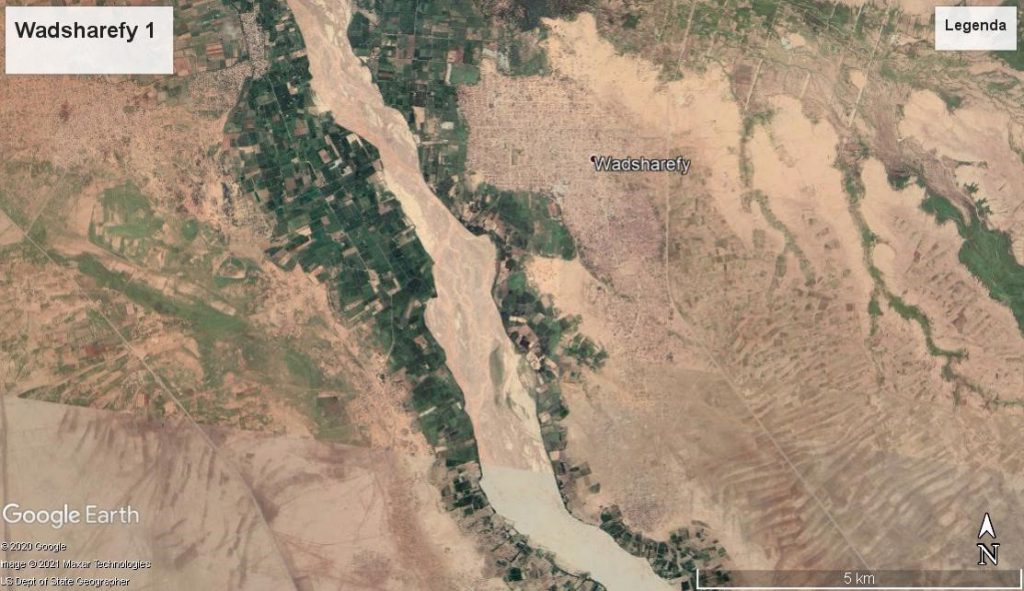

In the present day, various irrigation techniques are available and also suitable pumping installations to use the water of the Blue Nile. Via Google Earth it is an exciting journey to fly from the Tana lake to the GERD. Everybody can choose and adjust the height yourself if you want to see more details in the settlements along the Blue Nile. Sometimes you may suspect that an important amount of water is used for the production of food or in the households of the families for humans and animals.

In the Blue Nile catchment area, 70% of the current production of the cereals is grown. That’s about a quarter of total grain production in Ethiopia. Tef is used in the kitchens for the preparation of injera . That is the basis of the diet for the vast majority of the population. Of the agriculturally suitable land in Ethiopia, 8.5 million hectares are used for the production of tef. 160,000 hectares are used for the cultivation of vegetables.

A country that is regularly ravaged by famines will mainly want to ensure self-sufficiency for its population in villages and towns. Egypt is heavily dependent on food imports and certainly opposed if the supply of water in Lake Nasser is limited.

Ethiopia, with a similar population as Egypt, has suitable land and water to be self-sufficient for the necessary foods. It is a political choice in Ethiopia to lease usable land to foreign investors. Beneficial for the Treasury, but risky for the food of all residents in Addis Ababa and other regions.

In January 2019, an extensive article was published in the journal Frontiers in Environmental Science, by Mariam M.Allam and Elfatih A.B. Eltahir entitled “Water-Energy-Food nexus sustainability in the Upper Blue Nile (UBN) basin”. This article pays close attention to the impending conflict between Ethiopia, Sudan and Egypt over the management and use of the waters of the Blue Nile. Egypt and Sudan also invoke historical agreements that were already established under British authority in colonial times before 1950. The then Emperor Haile Selassi or his predecessor were not involved in the distribution of the Nile Water. Ethiopia may defend that all the water that falls inside this country, is available to be used for the production of food and electricity for her population.

This article raises the complex relationship between water, food and energy. Until 2019, the Blue Nile supplied about 60% of the water that becomes available through the lake Nasser for the production of food and energy, for the benefit of a population of 110 million people in Egypt. In the master plan for the management of Nile water, Ethiopia has included the construction of 11 water basins in the catchment area up to the GERD dam. These basins can greatly increase the production of food, especially tef, fruit and vegetables. But these basins could extract 7.6 km3 of water per year from its possible use in Sudan and Egypt.

The optimal GERD model assumes a regular water flow of 3 to 4 km3 per month. In the summer months, the demand for electricity is higher. Furthermore, variations in precipitation are to be expected in this catchment area. Based on the developed models, GERD can supply an additional production of 1000 GWh of electricity.

This requires in Ethiopia a restriction of the available water for irrigation. Mostly used for the production of tef, fruit and vegetables. Two main options are still possible:

- Land and water as a priority and optimal use for agriculture on the basis of precipitation and irrigation for vegetables, fruit, coffee and other products and also for the production of electricity in the GERD

- Use of water for agriculture and electricity production, based on the optimum net yield of the GERD and limiting a conflict with Sudan and Egypt

The storage of water in 11 water basins will limit the production of electricity in the GERD. Calculations show that this will only provide a financial advantage for three basins (Ribb, Gilgel Abay and Dabana). Electricity could be sold to Sudan and other countries. It is clear that the optimum availability of water can provide more nutrition, to limit the risk of food shortages in Ethiopia. But the production of more electricity also offers opportunities for the manufacture of industrial products and the fulfilment of the wishes of households and institutions in towns and villages in order to have regular electricity in Ethiopia.

If Ethiopia chose to use the estimated amount of 7.6 km3 of water for the additional production of food, there could be a serious conflict, especially with Egypt. This country with a similar number of inhabitants is almost entirely dependent on the amount of water that will be poured into the Lake Nasser. The restriction of 7.6 km3 on an annual basis in the coming years, may lead to a long-running conflict between the two major powers Ethiopia and Egypt, with the greatest risk that the GERD could be attacked by Egypt.

If this amount of water of 7.6 km3 is used for the additional production of electricity, this will generate more money for Ethiopia than the production of food. This can provide a positive result for the exploitation of additional electricity in Ethiopia itself and the sale of this energy to Sudan and Egypt. But the increase of the population in Ethiopia and Egypt, horizon 2040, will significantly increase the demand for water and also for energy.

CONFLICT ETHIOPIA – TIGRAY – ERITREA

The brutal conflict between Ethiopia, supported by Eritrea, and the Tigray region has forced more than 50,000 people to flee to Abdurafi and also to Sudan. The small town of Abdurafi is located on the river of the same name and forms the border between the Amhara and Tigray regions.

In the immediate vicinity, a tributary from Tigray pours its water into the Abdurafi River. It then winds its way through the north-east of Sudan with the Atbara River as its final station. This Atbara is an important tributary of the Nile. Via Google Earth you can easily follow the basin of this tributary in Tigray, the Abdurafi and Atbara from an altitude of about 1000 meters.

A significant proportion of refugees from the Tigray region have ended up in Abdurafi. These may be predominantly Amhara families, as this city is located in the Amhara region, on the Tigray border.

The reception of numerous refugees in an existing settlement is not easy, but it is the most logical option for families who at least hope to have access to water, food, shelter and medical care. In 2018, there were several ethnic conflicts in Ethiopia, especially in the Oromia region. In that year, there were 900,000 refugees in Ethiopia, mainly from South Sudan, Somalia and Eritrea.

Emergency aid from Médecins Sans Frontières

“In July, we launched one of our largest emergency operations of 2018 worldwide, when ethnic violence near Gedeo in the Southern Nation, in the Oromia region, escalated and hundreds of thousands of displaced people were left without basic services. When our teams arrived, people were living in overcrowded conditions. They slept on the ground in abandoned buildings and suffered from diarrhea, intestinal parasites and other infections. We supported several hospitals, health centers and mobile clinics until the end of the year.”

Where do you house 20,000 refugees in a city of about 18,000 inhabitants? There are numerous small stalls in Abdurafi that could possibly be used for the most urgent needs. Water is available in the river of the same name. Some of the Amhara families could move to Gondar and also to Bahir Dar and Addis Ababa. A significant other influx of refugees from Tigray and Eritrea may have moved to Sudan. Possibly to the refugees camps Shagarab of the UNHCR or to Kassala and Port Sudan.

Dramatic attacks are also taking place in other regions of Ethiopia. Ethnic tensions will force many households to leave their current homes and seek safer accommodation elsewhere. The compulsive pursuit of a federation of regions with their own culture and language can evoke memories of the regime of the DERG under Mengistu. After the murder of Emperor Haile Selassi in 1975, extreme cruelty was attempted to impose a communist system on all residents. The fact that the federal army brutally stormed the capital of Tigray in 2020 is likely to provoke fierce resistance in this region. Tigray’s leaders spent 20 years in Addis Ababa led by Meles Zenawi. After his death in 2012 at the age of 57-in a hospital in Belgium-he was praised by many leaders in the US, the EU and AU. But was also reviled by various opponents in Ethiopia who were given little room to make their voices heard in their regions or in Addis Ababa. Especially in the largest region, Oromiya, there was simmering resistance and dissatisfaction with his policies.

Figures on poverty in this country are also alarming in 2020. A quarter of the population lives below the border of poverty used by the United Nations. The 10 regions and the cities of Addis Ababa and Dire Dawa can determine their own policies in terms of food security for their populations. In 2020, the capital Addis Ababa had a population of more than 4 million. Region 3, Amhara, has about 20 million people, spread over numerous settlements.

Regio 4, Oromiya, crowns with more than 27 million people using about 40% of Ethiopia’s total land (1,135,000 km2). Together with region 10, Sidama (15 million), region 3 , 4 and 10 represents more than half of the total population in Ethiopia by 2020. Sidama can use the water of the AwashRiver, but Amhara and Oromiya are mainly dependent on the tributaries of the Blue Nile. The water may be used for irrigation of their fields in this Nile catchment area. In northern Ethiopia, the water is poured into the Atbara River via the Tekeze River,which in turn dumps the water into the Nile, north of Khartoum. Farmers in Ethiopia and Sudan pump this water out of the tributaries for irrigation on their fields.

After a deep fall for power generation, passing the GERD, water flows further towards Khartoum and then to Egypt. From the GERD to Khartoum and also in the North of Sudan to lake Nasser in Egypt, there are many farmers who want to take advantage of the Nile to irrigate their fields. Filling the enormous lake of the GERD in the coming 7 years shall limit the storage of the water in lake Nasser.

It is therefore quite understandable that the farmers in Egypt are seriously concerned about the amount of water that will become available for the irrigation in the narrow strip of fertile land in this Nile catchment area. Only 3% of Egypt’s total territory is suitable for the production of agricultural crops. The Government in Cairo has therefore followed the construction of the GERD in the past ten years and will not accept the filling of the GERD lake in the coming seven years, as announced by the Government in Ethiopia. Filling the GERD lake in 12 or 15 years offers could be accepted by Sudan and Egypt.

More water in favor of Egypt could also be delivered, if the old plan to realize a canal in the White Nile. Especially to limit the evaporation of water in the colossal swamp in South Sudan. A comprehensive and costly project but possibly an opportunity to limit the discontent in Egypt. Furthermore, this canal project could offer also new perspectives to the numerous Dinka and Nuer families that are now living shabby lives in South Sudan by 2020.

In Ethiopia there are several tributaries and streams that drain the water from the highlands to a large extent to the Blue Nile. Virtually, that’s easy to look at. There are several settlements along the long Beles River where the farmers can pump water to their fields. Each village could construct a lake upstream in a tributary of the Nile and then let the water run down to their fields.

In regions where there is regular scarcity of tef, sorghum, fruit and vegetables, farmers could self-regulate their need for water for their own use. The region can also take the initiative to create some storage lakes in this important BELES river. Why should they care about the lack of water in Egypt? The Federal Government of Ethiopia can conclude an agreement concerning the filling of the GERD lake with Sudan and Egypt. Without the support of the farmers in this wide Nile catchment, such agreement seems like a paper document. Solidarity can be expected between farmers in the village. Caring about the fate of families in other countries seems like an illusion. While the virus COVID-19 is sweeping all over the globe, every country is desperately looking for vaccines. The shirt seems closer than the skirt in cases of a risky shortage of medicines or food.

The high mountains of Ethiopia, with the highest peak being the Ras Dashan at 4550 m, captures a lot of water. Then it is mainly transported via numerous tributaries to the Blue Nile. Oil, gas and minerals are considered to be the property of the country where these minerals could be exploited.

Ethiopia may also argue that the water flowing to the GERD, can be used by the country itself for the production of food and the generation of electricity. Egypt has offered big properties of agricultural land to foreign investors who produce a lot of vegetables and fruits. These products are mostly consumed in Europe, in the Gulf States and Saudi Arabia.

Why should big investors in these countries, who sell oil and gas on the world market and wallow in great luxury, make profit of the Nile water while millions of people in the Horn of Africa- in bitter poverty- spend their lives?

The population in the four most affected countries in the Blue and White Nile basin, Egypt, Sudan, South Sudan and Ethiopia, is expected to increase by 2 to 3% each year. For Ethiopia, this is likely to double its population over the next 20 years. What will be the future of the children who are born in 2021 in Ethiopia, in terms of nutrition, shelter, education and health in these coming 20 years? Families can move to another rural environment in Ethiopia, with better opportunities for their livelihoods. Young people can also try their luck in an urban environment, in order to better educate and find a suitable job.

Those who turn their backs on their old and familiar surroundings will plunge into a game of chance with winners and losers. Especially those who try to seek refuge in Europe, Asia or America, coming from Africa are often described as fortune seekers. Their courage can be appreciated, but on their trek they will encounter numerous obstacles, sometimes with fatal outcomes. Staying in a refugee camp for many years is certainly not a luxury. Crossing the Mediterranean is a dangerous undertaking, while the best reception often means a long stay in an asylum center in Europe. More than half of these migrants are sent back to their countries of origin; a quarter are estimated to disappear into the illegal circuit. Those who do obtain legal status will often be considered as foreigners. Equality and respect for each other, is too often still a long way off in Europe and the United States. Only a small minority who usually come to Europe, on the basis of an education, manage to live here satisfactorily for themselves and their children for the duration of their stay.

Internal conflicts in Ethiopia

Ethiopia’s 10 regions were created on an ethnic basis. In region 2 the Afar prevails, in region 11 the Tigreërs, in region 3 the Amharas and in region 8 the Oromos. Especially after 2000 , numerous ethnic conflicts arose. These threaten to seriously disrupt the political climate in Ethiopia in the coming years.

In particular, the two largest regions (Amhara and Oromiya) will have to compromise to ensure the livelihood of their population, horizon 2040. It is likely that many internal migrants will try to build a better life in these regions. Because the opportunities there seem more favorable, especially in the urban and rural environment of Addis Ababa, Adama (formerly Nazaret) and Debre Zeit. Also in Dire Dawa (Harar region) supported by the renovated railway line who passes from Addis to the port of Djibouti.

In a bird’s eye view you can follow the catchment area of various tributaries of the Nile. The existing settlements could be given opportunities to use the water and produce more food with better seeds for all families who will live their now or in the future. Vegetation in this catchment area requires protection to limit erosion of fertile soil. Experiments elsewhere in Tunisia and Niger have sufficiently demonstrated that vegetation can recover sufficiently in a few years if the inhabitants are willing to limit their livestock on the common pastures. This can be managed by each settlement itself, by striking a balance between the vegetation available and the number of animals of all families. Each family should accept a limited number of cows, sheep or goats that can be admitted to these pastures. Of course, this process of restoring ecological balance can be further promoted by planting hedges and dikes with the aim of preventing the erosion of the soil and retaining rainwater for a longer period of time. This will also have a positive effect for a more regular drainage of water to the Nile. Self-management of its own land offers good opportunities for every settlement to avoid a looming shortage of food.

In recent decades, it has proved sufficient that the central government in Ethiopia did not have the real power to avoid famines on a large scale. Emperor Haile Selassi did not wish to inform foreign countries in 1973 about the absurd famine in his country. The DERG regime has also tried to force farmers to move to other areas where the opportunities for exploitation are better, but without taking into account local culture and traditions. Under Meles Zenawi’s dictatorial regime, foreign investors have been given ample opportunities to lease suitable land for a long term. The local farmers sometimes are exploited as poor paid workers. Space was also given to China to build costly infrastructure. Loans were taken out for this purpose, which the Ethiopian people will eventually have to repay in some way. The current government also seems to support this approach. Is China’s aim to use Ethiopia as a springboard for mining valuable raw materials for its industry? Does the farmer in Oromiya or Amhara region could benefit from this approach? Regional authorities can demand more participation in order to better protect the interests of their own people.

Large residential blocks were built in Addis Ababa after 2000. They are often apartment buildings, usually with six floors, where households with a reasonable income can get shelter. Mathieu does not know whether China played an important role in financing these complexes. However, in a Dutch newspaper in January 2021 he read a detailed article about tackling poverty in the Chinese city of Liangshan. In 2013, the number of rural poor people with an annual income of less than €530 was estimated at 93 million in China. Households in various hamlets in the mountains were moved to apartments in Liangshan. There was no lack of comfort in this new living environment. Children could go to school, there is a medical post and public transport, but there are very few opportunities to find suitable work. Every day each family have to be able to buy food, pay for rent, water and electricity. How to survive if money is lacking? Families often go back to their old hamlet to produce food in the private garden. A strategy that you can therefore question.

New apartments in Addis Ababa will not house families living below the poverty line in a rural or urban environment. However, many families in Addis Ababa have been forced to flee, due to an impending famine or ethnic conflict in some regions of Ethiopia. Usually this means a shelter for families in Addis Ababa or shelter in a refugee camp, in their own country or in Sudan. The UNHCR, the WFP and various private institutions, are doing their utmost best to provide basic facilities in these camps. Often attempts are made to offer the families who have fled, opportunities to make their own living as much as possible.

After extensive flooding in 1969 near Kairouan in Tunisia, numerous families had to flee the violence of this water. By purchasing a farm of more than 100 hectares, many families were able to settle down on a safe plot of 2000 m2. Thirty years later, Mathieu visited some of the families based there. He was surprised that they had mainly set up their lot to produce fruit and vegetables for their own use or sale on the local market. He also observed chickens, some sheep and often also a donkey for transport. Remarkably, trees had been planted for shade and fruit. Every family could tell their own story about these 30 years in this village.

Homesick for the old hamlet they had left, where their beloved parents and ancestors are buried, may still be bothering them. This mainly concerns the elderly; many young people had moved to a city in search of suitable opportunities to find a job. If that doesn’t work, you could return to your family. Many young people dream of leaving abroad, although they often realize that this is not feasible.

Households that have lost their homes and pushed to fled for a natural disaster, war violence, ethnic conflicts, famine or abject poverty are entitled to find a safe place to live. As early as 1948, all countries that are members of the United Nations (UN) signed the Universal Human Rights. Acceptance of this document creates rights and obligations of political leaders and bodies, in order to create opportunities for all people.

Having to remain dependent on benevolent fellow human beings, foundations or other institutions, for several years will mostly be appreciated by everybody in dire need. On this virtual journey along the Nile, Mathieu will pass through various regions where there are opportunities for sheltering people who are eligible.

He is not directly concerned with people who are looking for a better life in Africa, Europe or elsewhere in this wider world. His focus is on households and persons who are entitled to an urban or rural place of residence and are now below the poverty line, as applied in their region and country.

From his own experience he was able to explore various cities and regions in more detail. As an urban and rural planner from 1966 to 2006, he was also able to make a modest contribution to the spatial redevelopment of some districts in Tunis, Ouagadougou, Port Sudan and Addis Ababa. The increase of the population in Africa from 1.2 billion to 2 billion is likely to take place before 2040. Then half of this population in Africa will be located in an urban environment. Often this will at least double the current number of inhabitants in the big cities. Some existing metropolises such as Johannesburg, Nairobi and Kinshasa will then have to accommodate at least 10 million people in 2040. Lagos and Cairo are then home to more than 30 million people. Google Earth offered at a height of about 800 meters, an interesting image of settlements in cities and metropolises in Africa. The differences in prosperity cannot be determined, but these images do give an impression of the living environment.

In 2006, together with Martine , Mathieu visited Bahir Dar. This capital of the Asmara region has accommodated numerous refugees and migrants. By bike they could also explore the east side of Lake Tana and also took a boat trip to the other side on the way to the city of Gondar. They explored the area around Gondar with a young guide who wanted to show them the places, attractive to tourists. That was certainly interesting, but Mathieu also wanted to get an impression of how families lived there, who had moved to this city in recent years. They could have settled in the nearby surrounding area and managed to create a shelter. In a yard they were welcome to see how a woman was preparing injera. With tef you can bake a large pancake that is the basis for a favorite injera meal. You tore pieces of the pancake and dipped it in the sauces and added an extra bite. The differences in prosperity were mainly found in the variation of sauces and snacks. In this yard we were also allowed to taste the injera with a lean sauce.

It seemed clear to us that the hostess had to do her utmost best to serve at least one meal per day to her three children who were less than 15 years old. Her husband was killed in the 1998 war between Ethiopia and Eritrea. She had received 1000 Birr (80 euro) once as compensation. With this money she could have acquired this place of residence of approximately 60 m2.

For wood to prepare the meals she had to go out. Luckily, she could count on a neighbor who could look after her children. Her greatest wish was to be able to use a garden in the vicinity of Gondar to produce her own vegetables for the preparation of meals. Different families in her area could exploit such a garden. But she had to buy these products on the local market. Her own family had assisted her after her husband’s death, but now that her own children were growing up, she wanted to find an extra source of income. Working in her own garden with her eldest daughter a good plan for her. Now, 15 years later in 2021, it would be interesting to be able to check on the spot whether her plan was successful.

The River Valley of Gondar

During this visit to Gondar, they also walked with their guide to the river that winds its way through this city. They walked upstream in the nearby area, where suitable land was available for agricultural production on both sides. In the event of heavy rains, flooding would occur, but this would be beneficial for the enrichment of the soil. Often this land in the catchment area is used only for grazing livestock.

However, there are opportunities here to mark lots for families who want to exploit gardens, especially for their own use and sale of the surplus on the local market. Gondar is now a medium-sized city with more than 200,000 inhabitants in 2021. You may expect an increase of 10,000 to 15,000 people annually in the coming years.

Neither the Ethiopian priests nor the imams have little interest in encouraging the families to limit the child number to two. In other words, replacing the parents with a daughter and a son. This policy does seem to be pursued in China today. A lot of water will still flow through the Blue Nile before this choice to limit the child number per woman will become a reality in Ethiopia. Some informants stated clearly that the church and the mosque are both an obstacle to the development of their country.

However, the land certainly offers opportunities to allow disadvantaged families to at least escape famine by allowing them a plot where they can produce food themselves in the river basin. Over the centuries, people have settled on suitable land for the production of food in the vicinity of water. Now in 2021, the world can produce more than enough food for 8 billion people.

However, policymakers seem to pay little attention to the fact that around 1 billion people in this world do not have sufficient financial resources to buy enough food in a local market, in shops or directly from a producer.

Of the 1.2 billion people in Africa,an estimated 200 million habitants in urban or rural settlements are unable to serve a meal daily for their children and themselves. It is clear that different degrees can be distinguished between malnutrition and flagrant famine. Only in Tigray, the United Nations is convinced that in 2021 more than 5 million habitants are confronted with famine. The political conflict in 2020 between Tigray, Eritrea and Ethiopia, is the main reason that hunger is used as war weapon, to destroy Tigray families.

In Martin Caparros’ book, Hunger (El Hambre, 2014) he pays ample attention to the lack of food. In Niger, he spoke to Aisha, 30. He asked her what her biggest wish was: “I want a cow that gives a lot of milk. If I sell a little milk, I can buy the stuff to bake fritters. I will certainly never be hungry again with two cows.” In the Sahel the hunger is always present, but that is also true for various regions in the Horn of Africa. Mathieu will pay close attention to this on this virtual journey, in the great basin of the Nile. Dreaming that the manna could fall from heaven is not enough for thousands of mothers. They wish to be able to feed their children enough food every day. Also in Tigray in 2021.

Numerous rivers flow in the rainy season in the Horn of Africa and also in the countries of the Sahel, Sahara and Maghreb. Some permanently- other rivers are drying up, in the Sahara. Along the Blue and White Nile and their tributaries there are certainly opportunities for the production of food for families who have fled. Families who settled in a “spontaneous settlement” in the surrounding area of cities could also be eligible for resettlement on a voluntary basis. During discussions with various families, it turned out that the prospect of acquiring their own residential plot of approximately 600 m2 would encourage them to settle there and produce fruit and vegetables in their own garden. Main condition: water should be available in the vicinity of these gardens.

The precipitation that falls in the highlands of Ethiopia flows to a large extent to the Blue Nile. If you use all the water from these tributaries for agricultural production or for other farms, this shall reduce the amount of water flowing to the GERD dam.

In the pictures of this part of the city of Gondar, the catchment area of the river from north to south is observable. The available land seems suitable for use for pasture and horticulture. Suppose you can form small groups of about 20 households, to create a garden area of about 2 hectares. Any household could obtain a garden of 600 m2 for the duration of 5 years. With the option of prolongation after 5 years. The group could mutually assist each other in the heavier work, but still be able to carry out the production and harvest independently as much as possible. Trees and hedges could be planted on the remaining land to limit erosion. Exchanging experience could be a good boost for members of this group who have more knowledge to plant vegetables, herbs and other products in their garden. This could also strengthen social contacts.

With our young guide Samuel we stepped further into the skimming area of this river in Gondar. He said his parents had lived in a village along this stream and they moved to Gondar before he was born. That’s where his father worked in a sawmill. In this area there used to be many Falasyas (invaders in Amharic). These were Ethiopian Jews who had been lured to Israel and drawn into the land of the Palestinians. On the left there were a number of houses and we stepped on. The terrain was neatly divided into rectangular blocks of approximately 2000 m2. Mathieu wanted to know more about that. This reminded him of his experiences in Tunisia. It was previously mentioned that around 1970 he was involved in the distribution of more than 100 ha and the allocation of comparable lots of 2000 m2. Here in the surrounding area of Gondar, these plots were neatly demarcated with trees and shrubs. Interesting for families to pick wood for the preparation of meals and sell part on the market in Gondar.

He suggested Samuel to visit a family in this settlement. He could certainly find a family whom and how these lots were used. Mathieu also hoped to find out if water from the river was being routed to these lots via a clever construction. In a small dam you could collect water upstream and let water flow down through a canal. Mathieu had seen some useful constructions in Tunisia where families had managed to exploit the height difference and in this way, at no cost, let water flow to their fields. In this way, those who did so could certainly increase their production of grain, vegetables and harvest more.

The sun was shining. Two men were busy, talking to each other. When they saw us coming, they were certainly surprised that two tourists came with a schoolboy to get some air quite far outside the town of Gondar. Samuel kindly stepped on it and presented his words of greeting in the Amharic language. When he explained that these guests came from Amsterdam , it was clear that he informed them that he was on the road with these tourists as a guide. He must have also pointed out that he had already presented some beautiful sights in the old town. But these guests wanted also to explore the surroundings via the river. Samuel added that Mathieu had worked in Tunisia for eight years and had explored several countries of Africa and that he knew the cities of Port Sudan and Kassala – where he had visited refugees from Eritrea in a few settlements. This introduction was apparently more than sufficient, because they went into detail about the questions Mathieu then asked them through Samuel.

Not being able to talk directly to a local farmer in Ethiopia is a real obstacle. Mathieu had experienced this many times on all his treks in Africa. The oldest man told us that this site used to be owned by a wealthy family in Gondar, in the time of Emperor Haile Selassi. After Mengistu came to power in 1975, the family had fled abroad. As far as he knew, they had gone to the United States and stayed there. Under the DERG the tenants had to work together in cooperatives. Each member of the cooperative was given one or two plots, depending on the size of his family. They had both also been members of this cooperative. After the expulsion of Mengistu, the cooperative had survived. The board mainly took care of the maintenance of the water supply in their settlement, the supervision of the planted trees and shrubs and they tried to limit conflicts over the use of the common pasture land. Some members had sufficient resources at their disposal to buy a number of cows; others had only a few sheep or a donkey. In the dry season there had to be enough water available for the cattle as well. A cow guzzled more moisture inside than a sheep. How do you distribute equal rights on the limited grazing land of your cooperative?

In various settlements in the surrounding area, violent conflicts regularly arose, especially between members from different ethnic backgrounds. In the rainy season, of course, the water flowed down at full speed. Their cooperative could have built a barrier upstream to be able to funnel enough water to a spacious collection basin. Some of the water in this basin evaporated. The water was especially necessary for the water supply for humans and animals. If you also wanted to use this for irrigation, in favor of gardeners, for the production of food, then it was advisable to expand the basin or to build another. Now these plots were mainly used to grow the grains tef and sorghum. If you could sow these types of grain at the right time, at the begin of the rainy season, this usually yielded a reasonable harvest.

Unfortunately, there were also years when there was not enough rain and there was a meagre harvest. In some regions of Ethiopia, there was a serious shortage of food, especially for households that could not have maintained supplies. Famine would have been lurking. The members of their cooperative were well aware of this. This could also occur in the coming years because the annual precipitation could not be predicted. However, they realized that the destruction of the soil by felling trees and shrubs in recent years had a disastrous effect, also in the surrounding area of Gondar. We said goodbye to them with thanks.

The river valley to the south in Gondar

Our guide Samuel understood very well, that we were mainly looking along this river for plots of land where families could produce food themselves. The availability of water was, of course, an important advantage. That’s how we walked south along the river. Photo 5 shows very clearly that many lots were marked on the west side of the river in a residential area. This was a planned residential area, the size of each plot was approximately 250 m2. A clear difference from the distribution of space to the newly visited cooperative on the north side of Gondar. However, on the east side of the river a settlement had also been established where the plots differ significantly in size.

An uncle of Samuel had a plot on the east side of the river. He would certainly be willing to inform us in more detail about the use of these lots, which are very suitable for horticulture. Uncle Ibrahim was an affable, sociable man who enjoyed going out with us to these gardens. There was no co-op here. The land belonged to a prosperous family in Gondar. A long time ago, the emperor had allocated large lots to Ethiopia’s elite families. It covered an area of approximately 30 hectares. This wealthy family had allocated plots of less than 2500 m2 to 26 households and also allocated residential places to more than 100 households living along the walkable path.

Every year, all the tenants were expected to bring part of the harvest to this wealthy family in Gondar. The main difference between the equal distribution of space on the visited cooperative on the north side of Gondar and here on the south side was that the actual lots on the south side appeared to differ markedly in size, during our visit in 2006. It could be subdivided later on by the tenants.

The lot where Ibrahim lived with his family had a size of less than 300 m2; he also had a spacious garden of approximately 500 m2. He was living here for over more than 30 years. Even under the DERG he stayed here and continued to work in his garden. This was urgently needed because there were serious problems with food supplies at the time. He had grown up in a small village in this province. His parents had flocked to Gondar during the famine in 1973. His father should have settled here, along with other households of his old village.

He shouldn’t have lived closer to the river because his house could wash away in hellish rainstorms. However, you could grow vegetables, tef and sorghum there. Two gardeners had hit their own pit. Then, of course, you could harvest more vegetables; often twice a year. Foods that were urgently needed, especially in times of scarcity. No one had forced these tenants to set up a cooperative. This had often been the case in the distribution of land from large landowners. We thanked Ibrahim and then returned to our hotel. Upon leaving, Samuel said that the contribution to education he attended was a heavy burden on his parents. That was why he was available in his spare hours to act as a guide. He did show that this long walk through the river valley was also a discovery for him, where he had not been with tourists before.

By bus back to Bahir Dar

Within walking distance of our hotel was the Gondar bus station. That’s where Mathieu and Martine went, looking for a bus that would take them back to Bahir Dar. That wasn’t so bad, there was a bus ready for departure and they got in. The bus drove through a varied landscape with mountains and valleys. After more than an hour, the engine gave up and the driver had to choose a stop in the roadside. About 40 passengers got off and searched for a shady spot. We could not understand the driver’s explanation, but one of the passengers appeared happy to explain to us that the driver had made an appeal to send a replacement bus. That could take a while, so we also thought we could find a suitable nice place with a tree for shadow to enjoy the surroundings.

Our provisions were limited but with a bottle of water and fruit we could hold out for a while. Mathieu knew the stories of stranded travelers in Sudan and on trips in the Sahara. You always had to take into account that you could bump into an obstacle. Waiting can take a long time. Take a break to explore the landscape, with a view on the east side of Lake Tana! There was a lot of agriculture. What was being planted you could only suspect, probably a lot of tef and sorghum. It was a fairly flat landscape, arranged for a bike ride. The rivers and streams that discharged their water into Lake Tana certainly offered opportunities to direct water to fields for irrigation of fruits and vegetables.

While we had to wait there along the road, we were able to explore the area well. With our binoculars you could also see details, such as birds looking for food or water and then taking off again. May be they could get a fish out there. The space between the paved road where the bus was stranded and the river was apparently used as a pasture area for cattle.

Various agricultural products could be grown on the sides of this catchment area. If little water flowed through the river, you could probably find water at a depth of less than 10 m. With a pump and the energy of the sun, you could still produce quite a lot of food in gardens of about 600 m2.

Families who felt they should flee Eritrea or Tigray could stay there for quite some time in small settlements. It seemed possible that they, with some assistance, could then gather a significant part of the necessary food themselves.

After a few years they could go back to their village or town in Eritrea or Tigray. Mathieu has been able to walk around various settlements over the past 50 years in some countries of Africa, where numerous families lived in bad conditions. Sometimes you have no other choice and you have to leave the familiar environment. If your home is dragged along by a flood of water from a river or your supply of food is completely depleted to feed your children, or wartime violence and ethnic conflicts do force you to leave, then families will flee to find a safe place elsewhere.

There is no ready-made solution to these often extensive disasters. You are lucky if you can find a place to stay with families or organizations that are willing to allow you into their living yard or offer you a tent in an encampment. Usually these are only temporary facilities in Africa.

If you have sufficient own resources, you can manage to rent a place to live and possibly also carry out paid jobs in a village or urban area. In Ethiopia, more than 90,000 refugees, mostly from South Sudan, have been taken to camps where they depend on food aid. In the vicinity of the city of Kassala in Sudan, near the border with Ethiopia, there have been thousands of Eritrean refugees for many years.

By 2020, more than 40,000 refugees from Tigray and Eritrea are likely to have been taken to UNHCR reception camps.

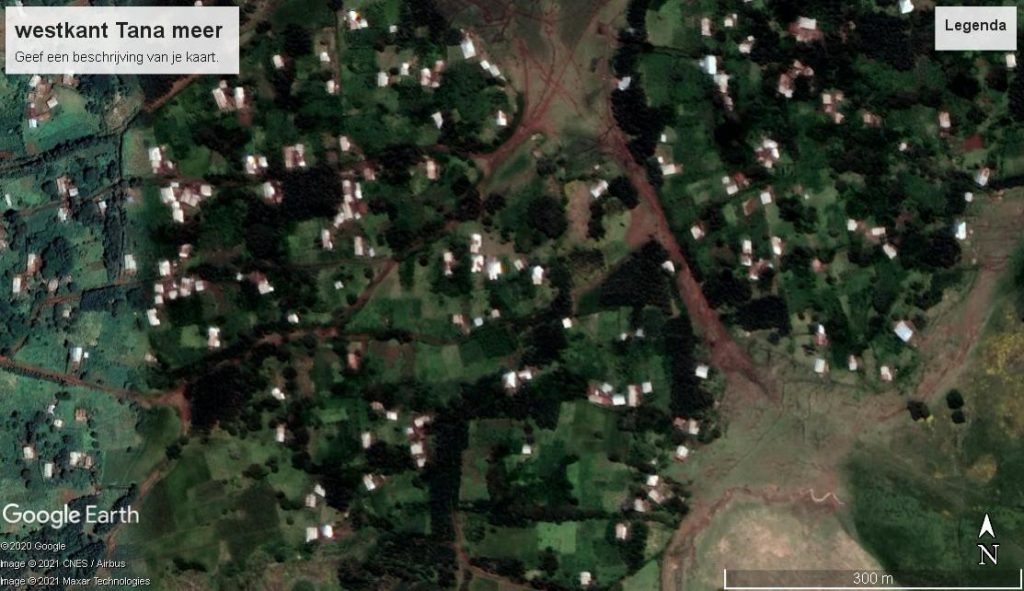

On their outward journey to Gondar, Mathieu and Martine had travelled by boat across the lake from Bahir Dar to the port of Gorgora. The captain would pick up a group of German tourists who would arrive by bus from Gondar. They also boarded a bus and travelled from Gorgora to Gondar. This bus went by the northwest side of Lake Tana to Gondar. From the bus they had seen a large settlement. Through Google Earth, Mathieu was now able to view this settlement more calmly in 2020. It seemed as if a zoning plan was designed for the spatial distribution of the land.

The residents could have realized their own shelter here. In the vicinity, they might also have been able to lease a lot to grow vegetables, grain and other products. In this way you could also accommodate refugee households, which could soon produce an important part of their food themselves.

In Gorgora they had to spend a night in a military encampment because there was no room in the only hotel, which was reserved for these German tourists who wanted to go back the next day by boat to Bahir Dar. Before leaving Gorgora, they walked in the immediate vicinity without a guide, before taking the bus to Gondar in the afternoon.

But now they were still waiting for a replacement bus to Bahir Dar. After two hours it came and the passengers were able to board again. Several seats were not occupied now- as a number of travellers had chosen to hitchhike.

An hour later, Mathieu and Martine were able to get off in Bahir Dar and went to the hotel in front of the Tana Lake. Early in the morning they saw the activity in the port . Numerous fishermen had gone out very early with their papyrus boat and were now returning. They got into a conversation with a researcher(Patrick), who told them that fish stocks were under serious threat and that in this large Lake Tana with an area of about 3700 km2 and a maximum depth of 14 m, the water hyacinth also advanced rapidly. In the Encyclopedia Brittannica you can find interesting data.

For example, it was assumed that more than 25,000 years ago the Dember- plains on the north side and the Fogera-plains on the east side were flooded and the Tana Lake was more than 10,000 km2. The most distant source is the Abbay and the lake is filled by the rainwater of 60 rivers. At the Tisisat waterfall, the Blue Nile plunges 42 m down. The hydropower is partly used for generating electricity.

On their bike ride in the surrounding area of Bahir Dar, they got a nice impression of the use of the probably mostly fertile soil. Tef and sorghum are also the most important cereals in this region, Patrick had informed us. The production of oilseeds and coffee beans was attractive for many farmers to earn income for their families.

Along the rivers and near the lake you could grow fruits and vegetables and sell them partly at the local market in Bahir Dar.

On the dirt tracks you could cycle well. In the rainy season from June to October it would be a slippery path. But in January you could cycle close to the lake and also continue along a river. Most strikingly, however, you cycled through planned neighborhoods on the north-east side of Bahir Dar for quite some time and then followed paths through a large “spontaneous settlement”. Where did these families come from? Had they gone from their village to Bahir Dar in the hope that they would be able to build a better existence there? Or was it mainly Amharic families who were threatened in other regions and sought safe haven near the capital of the Amhara region? Could they have rented or bought this place of residence from a farmer who could thus increase his income and then no longer had to plough this land with two oxen?

On this virtual trek, Mathieu is unable to give a reliable answer to these questions. This is an après-fiction story, wrote by him first in the Dutch language in 2020. Partly fiction, partly it corresponds more or less to reality.

Sometimes they got off their bikes to find someone who could show them the way to return to Bahir Dar. Although they did not speak the local language, you could always raise your hand and kindly pronounce “Fondouk Bahir Dar ?”, then you were pointed in the right direction.

At one crossroad, they were lucky to meet a man (Solomon) who had received training in East Germany, at the time of the DERG-regime. He had worked there four years in a sawmill. He had returned to his family in 1993 who lived in a village near the border with Eritrea. Five years ago he had moved to Bahir Dar because he hoped to find work here that matched with his experience in Germany. From a farmer he bought a lot of 800 m2. That allowed him and his family to produce herbs and vegetables and also keep a dozen chickens. Occasionally he could get a job in the construction of houses in Bahir Dar. Most of the families in this settlement could have bought their lot from a farmer who had different hectares of land- but didn’t have enough resources to buy machines to farm his land. The farmer’s two sons had preferred to try their luck in Bahir Dar. She seemed to have done a pretty good job of that. The families that had settled in this settlement in recent years came from various regions of Ethiopia. Solomon had never delved into the cultural background of his neighbors.

In the rainy season there was plenty water in the river. It was fertile soil on which you could produce many crops. Digging a well through 10 or 20 households would create additional opportunities in the months when less water flowed into the river. With a pump you could then produce fruits and vegetables.

Lake Tana and the fertile surroundings create ample opportunities for families who want to settle here to build a life. The colossal lake offers opportunities to promote fishing in a technically responsible manner. This requires training and transfer of knowledge in order to enable young people in particular to earn an acceptable income. The destruction of vegetation in this region of Ethiopia can be stopped by the planting of trees and hedges around the plots used for horticulture and the production of tef, sorghum, oil seeds and coffee. Along the 60 rivers that supply water to Lake Tana, spacious residential plots of at least 600 m2 could be issued, where households may produce a significant part of their own food. The construction of their living space and the planting of hedges will have to be carried out by the families themselves.

Ethiopia has been suffering from a large debt burden for many years. The rapid increase in the population over the next 20 years (from 110 to at least 200 million) in 2040, will require numerous efforts from all families to avoid famines on a large scale.

In 2020, it was reported that 40% of Ethiopia’s population is below the poverty line. Much help for the less fortunate part of the families will not be possible in the coming years. The United Nations has received only a quarter of the pledged resources to deal with shortages in food supplies by 2020. The still growing COVID-19 pandemic will not be conducive to encouraging donors to actually meet their annual contributions in the short term.

On this virtual journey along the Nile, Mathieu will pay little attention to outside assistance to limit famines in Ethiopia, Somalia ,Eritrea, Sudan, South Sudan and Egypt. The central question he asks himself on this virtual trek is : Which opportunities can be offered to households to reduce malnutrition and famine on their own in these 6 countries in the Horn of Africa?

In Cairo, a young man had taken two cans of fish; he was hungry. He was sentenced to six months in prison. Is that an absurd punishment? Had he no right to eat anything if hunger tormented him? Tunisia erupted in 2011 after the self-incineration of a young man. Local police said he was not licensed to sell his vegetables and fruits in the streets of Gafsa. On January 14, 2011, the people in Tunesia succeeded in driving the president, along with his corrupt wife, out of the country after two weeks of insurgency. Ten years later, another uprising is looming because poverty still exist in many towns and villages. Boys aged 14 to 16 get into shaky boats and try to reach Italy to roam Europe. Some of it may end up in the criminal circuit of the drug trade.

In Egypt, the example of Tunisia was followed and Mubarak was ousted from his throne. After correct elections, the Muslim Brotherhood managed to put President Morsi in the saddle. But the army of Egypt saw its chance to take all the privileges and actually pursue a dictatorial policy. Anyone who resists disappears into a less comfortable prison. The number of prisoners in Egypt is estimated at more than 60,000 by 2020. This regime can probably hold its own for many years with broad military support from the US and the EU. There is no shortage of generous arms supplies from the USA, Germany, France and the Netherlands. It is now estimated that 60% of Egypt’s 110 million people now live below the poverty line. Malnutrition is widespread. If Ethiopia and Sudan start using more water of the Nile to promote food supplies in these countries this approach could have serious consequences for the population in Egypt.

Egypt’s arsenal of weapons is now such that the military leadership in Cairo may decide in the coming years to take over the management of the Nile Water by force.

Instead of buying weapons, more attention could also be paid to use the water of the Nile in a more effective way. There are certainly opportunities to increase food supplies in Ethiopia, Sudan and Egypt with the amount of water from the Nile. More attention to the restoration of vegetation, especially in the highlands of Ethiopia, could potentially reverse the negative spiral over the next 20 years. This would also provide many opportunities for the promotion of employment in various areas of Ethiopia.

Arms supplies are particularly important for large companies in the US and EU. The EU, in particular, will have to be aware of the scenario of millions of refugees and migrants, wanting to settle in Europe peacefully or by force over the next 20 years. Actually in 2020, the aim is to stop this flow of refugees and migrants by providing mainly Turkey, Libya and Niger with resources to prevent refugees and migrants from leaving . However, the EU-Commissioner for Migration Ms. Yiva Johansson made her views clearly known in an interview ( published in the Dutch newspaper Volkskrant, 28 January 2021). She argues that the migration debate has been poisoned. Europe needs migrants, because this continent is ageing. Not only higher educated people, but also lower educated people. In 2019, the EU brought in 1.1 million migrants from outside the EU. This number must increase substantially, because demographic developments force it to do so, she notes. There are large staff shortages in healthcare. The EU is losing its attractiveness to higher educated people. Racism and the poisoned debate about migration make them choose other countries. No EU Agency is allowed to participate in pushing back migrants, as observed by informed journalists and volunteers. A statement that deserves wide attention in all EU countries!!

Up to 40 million inhabitants in metropolis GGBD in 2040?

There could certainly been lodged 200 million people in 2040 in this vast country of Ethiopia. There’s no shortage of space. If a summary calculation is based on an average of four persons per household, this requires 50 million lots for a population of 200 million. If you continue with an average space of 600 m2 per plot for house and garden, it is feasible to set up at least 10 plots per hectare (10,000 m2) spatially. This will require a total area of 5 million hectares of suitable land to provide shelter for 200 million people by 2040. High-rise buildings do not seem attractive to the vast majority of the urban and rural population.

It can be expected that by 2040 approximately 50% of the population is living in an urban environment and 50% in villages in rural areas.

An important part of these 200 million people, say 20%, could potentially be located in a new rural-urban metropolis of Gondar – Gorgora – Bahir Dar (GGBD). Is it feasible to create this metropolis for 40 million inhabitants in this so- called GGBD around the Tana Lake? Today, less than 5 million people live in this spacious agglomeration, and these 5 million live mainly in the urban and rural surroundings of Bahir Dar and also in Gondar.

If, by 2040, some 40 million inhabitants have found shelter in the metropolis of GGBD, then, in addition to the already existing living places, numerous new plots will be needed. Here every household, at an average of four people per family, could have or obtain a plot. A total of 4 million lots are then needed to provide this urban and rural population of 40 million people with their own place of residence. If possible with a garden to be able to produce some of the necessary foods yourself. The surface of these plots could be different per location. That needs to be studied.

If 1 million hectares of land is available to mark 10 million residential plots, then it seems feasible to establish 40 million inhabitants in this metropolis of GGBD around Lake Tana by 2040. A quarter of this population (i.e. 10 million) could suffer from a lack of food and drinking water for humans and animals every year. This means severe malnutrition for their children and also for all adults.

If a household of four people (father, mother, son and daughter) has its own lot of 600 m2, then they can be considered able to produce a large part of the necessary foods themselves for their own use. A surplus can be sold at the local market. The quality of the soil can be improved annually with composting for the production of food. However, there will have to be access to a quantity of water to prevent dehydration and withering.

Setting up plots in the vicinity of Lake Tana or along a river or stream is certainly the most likely to succeed in avoiding malnutrition and hunger. It sounds simplistic. You would expect that the millions of dollars and Euros sent in the direction of the Horn of Africa and the Sahel by public and private donors over the past 50 years would have created a basic provision for low-income households. But that doesn’t seem to be the case. On a small scale, there have certainly been a number of attempts, but the vast majority of households have missed these opportunities. And that affects more than 80% of the less fortunate. Betting on the strong in these countries seems to have been the strategy until 2020.

In 2021, you can easily observe the actual situation on the spot via Google Earth. Families who have already moved to the future metropolis of GGBD have managed to settle there. A river flows through this residential area and the water plunges into Lake Tana, about 500 m to the right in the photo below. The soil seems to be of good quality to grow products and is probably also suitable for the cultivation of coffee.

It is interesting to view a satellite image of the same area via Google Earth in 2009. The settlement shows a similar picture in terms of buildings. The first photo was probably taken in the rainy season and the second image in the dry time.

In this second photo, the plots for agricultural production are clearly visible. During their visit in January 2006, Mathieu and Martine did not explore this west side of the Tana Lake. Looking for more information about the origin of these families, the acquisition of their place of residence and the size of the available space for the cultivation of agricultural products, some studies were published on land use at the University of Bahir Dar . In January 2021, the following article became available there. Three researchers , Alayu Haile Belayneh, Kidane Giday Gebremechin and Yemane G. Egziabher, published in the International Journal of Agronomy (2021 – (7) : 1-8) an interesting article.

“ Role of Acacia seyal on selected soil properties and sorghum growth and yield: Case Study of Guba Lafto District – North Wollo, Amhara National Region Sate.”

The yield of sorghum under these Acacia trees is significantly less than the harvest in the open field. However, this limits the washing away of fertile soil. Rainfall is 800 to 1100 mm per year. This falls mainly in the summer months and there are also some showers in the winter. There are small, mixed farms with an area of 0.4 to 2 hectares. Sorghum and tef are the most important cereals they grow; they also have some cows, sheep or goats. The researchers are well aware that the population is increasing rapidly.

The production of food cannot keep pace with this. It concerns rain-dependent agriculture, without certainty that the water is available from sowing to harvesting sorghum and tef.

In the periphery of Addis Ababa, Mathieu, together with Gullilat, had visited several “Peasants Associations” in 1995 and spoken to a number of farmers. During the DERG period they had been given access to a plot of 2 hectares. They were not allowed to sell this land, but their children could continue to live there and participate in the family business.

Most of the children had left for a residential area in Addis and had no interest in farm of the family. However, if they did not find a place to live in this metropolis, sometimes they could return to this home in the village of their parents.

Around Lake Tana the influx of migrants and refugees may be considered in a positive way. You could assume that small farmers are willing to lease lots to candidates who give up part of their harvest or pay a rent with money. This process seems to be in full swing. A farmer with a plot of 6000 m2, may be willing to lease 5 lots of 600 m. If he digs a well on his own property, this reservoir would certainly be useful for his family, the cattle and also for his tenants . This is essentially the basis for the emergence of many “spontaneous” settlements.

Even after sowing sorghum and tef, the small plants could be sprayed in the first weeks, if necessary with watering cans. Also suitable for fruit and vegetables. Then the yield of these products will be higher. Some farmers may consider building small collection basins in tributaries and streams to store 5 to 10m3 for use in the dry period. That could increase the production of needed food.

Often people are able to save themselves, certainly also in Ethiopia. Waiting for support from public or private funds, is a uncertain adventure for a farmer.

It seems possible to produce enough food for all households in this rural-urban metropolis GGBD for a population of 40 million inhabitants. The less fortunate households can also be spared serious malnutrition and famine with a plot of 600 m2. Solidarity can only be achieved if each family acquires a right to live in order to have a piece of land with the necessary space to live there and produce an important part of the food themselves. This strategy could offer many chances to millions of households in Africa.

The neoliberal promise that wealth and income gains would trickle down to those at the bottom was fundamentally spurious.

Joseph Stiglitz (2021)

Thomas Piketty’s books provide many information and recommendations to move the beacons in Europe and elsewhere where the neoliberal epistle has been preached for many years. With all the excesses this strategy has created a society from super-rich to very poor people in this world. Change is urgent.

In his latest book: CAPITAL and IDEOLOGY (2019), Piketty present different proposals that could lead to significant shifts on this globe. There will certainly be fierce debates on the distribution of wealth and justified incomes in the coming years.

These building blocks for participatory socialism in the coming years could potentially be widely applied in Europe. Waiting for all 27 EU Member States to agree on major course changes takes too long, Piketty argues . The existing right of veto of all countries is a too powerful weapon against the possibility of taking needed decisions. A limited number of countries within the EU could take the lead; other countries could then join. An important initiative could be taken by the majority of European countries, as far it concerns the minimum and maximum welfare for all their families and individuals. The poorest level is mostly defined in different countries. Why not define the maximum of the capital, allowed for each person in these countries? If the maximum could be agreed in 2022 , for example on 5 million Euro per person , the surplus of the available capital could be used by each country as a fund to restore the economy in many countries of this world after this COVID 19 pandemic period. This is certainly an attack to limit the wealth of very rich people, but it seems a logic choice for most of the countries in Europe.

The results of this comprehensive examination by Piketty’s team, needs to receive wide attention in Europe and many other countries in this world. In the next decade there could be a squeeze on the accumulation of capital. Dissatisfaction among young people, whether highly educated or not, is also growing in the EU. The beacons seem to have to be really rescheduled, after this COVID-19 pandemic in this divided world.

European solidarity in health has never been so urgent and imperative, in view of member states’ failures to manage the pandemics. But the need has been evident for years, confronting common challenges in vaccination, antimicrobial resistance and mobilisation of the scarce resources required for complex treatments while ensuring nobody is left behind in access to quality healthcare.

Social Europe, 14 January 2021

The COVID pandemic is continuing, also in 2021 in Europe and elsewhere on this earth. If it is not possible to reach an agreement with 27 Members of the EU on this issue, why should 8 or 10 Members not be able to conclude a mutual treaty in order to achieve the chosen objectives in the coming years?

In 1972, the Club of Rome published an alarming report, “Borders and growth” on the state of the world, in which rapid increases in the population, depletion of soil and raw materials and also the climate received ample attention. Topics that deserve wide attention even after 2020. But the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak has brought virtually the entire world into turmoil.

The consequences of this pandemic in the coming years will have to be seen. Some vaccines are now available to combat them. However, mutations are feared. Virologists, in particular, are not comfortable with that. The WHO strongly defended the distribution of vaccines to all countries. Rich countries are covered first. In Africa, millions of people still have to wait a long time.

On this virtual trip along the Nile, Mathieu will also pay attention to the consequences of this pandemic for the locals. The authorities have announced various measures to limit people-to-people contacts. However, an important part of the society in the Horn of Africa and Egypt depends of tasks and activities to be carried out in order to generate income for their basic existence. What the spread of Covid-19 and possible various mutations means for this cannot yet be determined. If there is enough food for sale at the local markets or in shops, you still need to have the means to buy this food. It lacks that, resulting in malnutrition and finally famine for many households.

Although many leaders in Africa have praised socialism with a lot of words, in practice it often appeared to be suspended. This needs a more careful study to evaluate the applied attempts and results, pursued in the past 50 years in the Horn of Africa, Sudan and Egypt.